Each of these procedural mechanisms brings different benefits and challenges for claimants and – by extension – for their funders. In this article, we explore how each such mechanism has evolved over recent years, the ways in which claimants are testing the limits of each, and our predictions for key developments in 2023.

The rise and rise of the CPO regime

The past year has seen the continued growth of the collective proceedings regime established by the Consumer Rights Act 2015, which enables claimants to band together to seek redress for certain breaches of competition law, subject to the making of a collective proceedings order ("CPO") by the Competition Appeal Tribunal ("CAT").

Collective proceedings before the CAT offer claimants two particular benefits. First, they may be brought on behalf of each individual falling within a defined class who does not actively "opt out" of the proceedings, enabling class representatives and their funders to avoid the significant upfront costs of building a book of interested claimants. Second, the CAT may make an award of damages (an "aggregate award") without assessing the damages recoverable in respect of each individual claim, which (on the face of it at least) should greatly simplify the process of establishing damages across the class.

After a slow start (the first CPO was made only in 20211), the CPO regime is now an established feature of the UK litigation landscape. We are in particular seeing an influx of applications for CPOs against "Big Tech" firms. By their nature, anticompetitive behaviours online easily affect thousands or even millions of consumers – perfect territory for collective proceedings. By way of example, collective proceedings are on foot against Apple2, Google3 and Amazon.4 Sony5 and Qualcomm6 also find themselves in the firing line. We expect to see more such claims filed over the next twelve months.

We have also seen claimants creatively framing a variety of claims as "competition" matters in order to bring them within the ambit of the CPO regime. An example is the use of the CPO procedure to bring proceedings for the alleged abuse of market dominance by Meta in respect of the personal data of 44 million Facebook users.7 The claim alleges that Meta abused its dominant position by making access to Facebook contingent on provision of users' data, which was then monetised via advertising.

In its certification decision, the CAT found that the applicant had not provided a satisfactory blueprint for an effective trial of the issues. It stayed the proceedings to enable the proposed class representative to file additional evidence, failing which the application will be rejected.8

The problems centred around the proposed methodology to assess whether the class members suffered any compensable damage and, if so, how much. The Supreme Court in Lloyd v Google considered related issues, and ultimately concluded that it raised insuperable difficulties in the context of a CPR 19.8 representative action (which we address further below). If the CAT in Meta ultimately reaches a similar conclusion, it may effectively close down the use of the CPO procedure as a potential alternative avenue for obtaining collective redress for privacy claims.9

We also expect to soon see at least one attempt to use the CAT's CPO regime to advance an ESG-related collective claim. A claimant law firm has recently announced its intention to bring a CPO application arising from alleged unlawful discharges of untreated sewage and wastewater into waterways; the application is presumably based on systematic failures relating to sewerage discharges which resulted in increased customer charges, reflecting an abuse of dominance (see our article on this topic). Any boundaries drawn in the CAT's decision will be watched with great interest since success on certification on this point can be expected to give rise to a swathe of ESG-related claims by way of the CPO procedure.

The more the merrier

One alternative to the "opt-out" mechanisms described above is simply to name large numbers of individual claimants in a single Part 7 claim form. This approach requires claimant law firms and funders to undertake an often time-consuming and expensive upfront book-building exercise. However, such claims are not limited to competition matters, and there is no requirement to satisfy any "same interest" test. Instead, CPR 7.3 simply provides that a single claim form may be used "… to start all claims which can be conveniently disposed of in the same proceedings."

The flexibility of this principle was demonstrated by the recent decision in Municipio de Mariana v BHP Group plc10, in which the Court of Appeal granted permission for some 200,000 Brazilian claimants to pursue BHP in England for damages caused by the collapse of the Fundão Dam in Brazil in 2015. The claims were brought on a single claim form, and were struck out at first instance in part on the basis that they risked being "irredeemably unmanageable" and would have led to "utter chaos". However, the Court of Appeal found that no such conclusion could be reached safely at such an early stage, and that the proper time to consider the manageability of the claims is at the case management stage. The claims have therefore been allowed to proceed for the time being.11

Such claims will continue to face significant procedural hurdles. However, Municipio de Mariana indicates that the English Courts will at least not strike out claims at an early stage merely because they involve very large numbers of claimants. The decision may therefore indicate a possible alternative means effectively to bring collective claims.

Group Litigation Orders

Another alternative approach to the bringing of collective claims is the Group Litigation Order ("GLO"). A key feature of GLOs is that they are an ‘opt-in’ procedure; in other words every claimant must individually make their own claim. The GLO then enables claims giving rise to "common or related issues" to be case managed together, with determination of the common issues, which then bind all members of the group, achieved through the trial of lead claims.

GLOs are a longstanding feature of the English collective claims landscape, and are an important vehicle for the management of multiple claims, including in the ESG space.12 The requirement that all claimants actively file their own claim (ie there is no "opt-out" mechanism), as well as a concern among claimants that they may lose a degree of control over the conduct of their own claims if they are combined with others under a GLO, is doubtless the reason why there is such interest amongst claimants in alternative "opt-out" mechanisms. Nonetheless, GLOs remain an important tool for the effective case management of group proceedings before the English courts.

Introduction

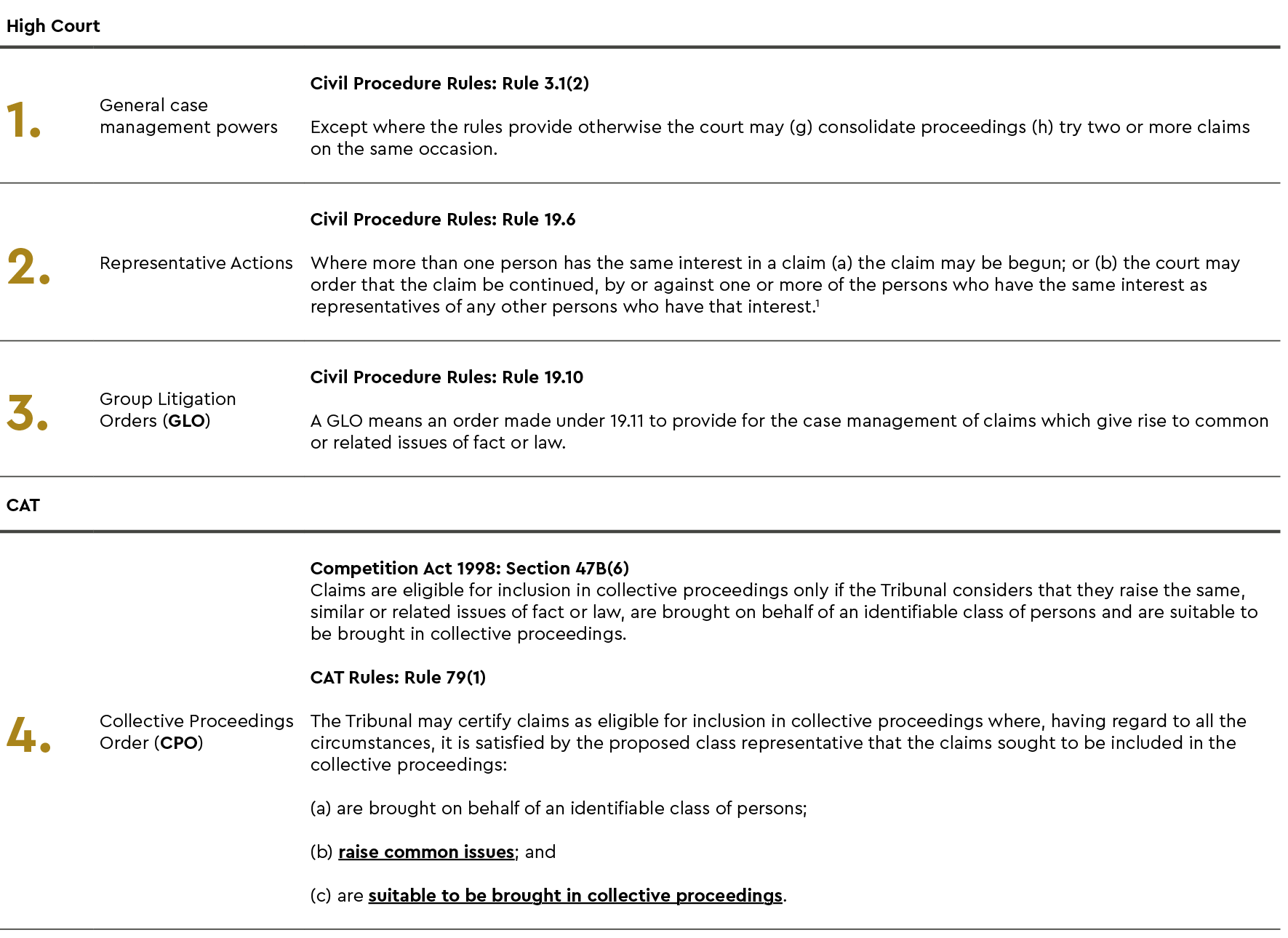

Collective claims (also known as "mass claims") allow groups of individuals, ranging in size from a small group to many millions, to seek redress collectively in a single set of proceedings. There are various procedural mechanisms for the bringing of collective claims in England & Wales (see Fig. 1), including: (a) the naming of large numbers of claimants in a single Part 7 claim form; (b) the collective proceedings regime established by the Consumer Rights Act 2015; (c) representative actions under CPR 19.8 (previously 19.6); and (d) Group Litigation Orders under CPR 19.22 (previously 19.11).

Notably, GLOs have recently been used to manage claims brought in respect of the "Dieselgate" scandal, concerning the use by the Volkswagen Group of so-called "defeat devices" to cheat on emissions tests of diesel engines used in its vehicles. Over 91,000 claims against Volkswagen were the subject of a GLO made in May 2018; those claims were reportedly settled for £193 million in May 2022. A further 120,000 claims have been brought against the Mercedes-Benz Group alleging that it had installed similar "defeat devices" in its vehicles; a GLO in respect of those claims was made on 8 March 2023. The proceedings are expected to proceed to a CMC in 2024.

Representative actions post-Lloyd v Google

The creative use of the CPO regime may in part be a reaction to the restrictive approach to CPR 19.8 representative actions taken by the Supreme Court in Lloyd v Google LLC.13

CPR 19.8 allows collective claims (which need not be limited to competition matters) to be brought on an "opt-out" basis. However, the absence of an aggregate award mechanism, and the need to demonstrate that all those represented hold the "same interest" in the proceedings, have limited the types of actions which are suitable to proceed under this form of collective redress procedure. As discussed in our 2022 Yearbook, the Supreme Court in Lloyd v Google was unwilling to erode or flex this "same interest" requirement.14

The recent High Court decision in Commission Recovery v Marks & Clerk15 was the first substantively to consider a representative action under CPR 19.8 since Lloyd v Google. The defendant (a firm of patent attorneys) had allegedly received undisclosed commissions when referring clients to a third party provider of patent renewal services; the claimant brought representative proceedings to recover the undisclosed commissions on behalf of all those affected by the practice.

The Court found that the claims satisfied the "same interest" test, and declined to strike them out despite some significant case management concerns. The decision may indicate that the Courts are willing to take an accommodating approach to representative actions notwithstanding the impact of Lloyd v Google. We therefore expect that claimants will continue to test the limits of CPR 19.8 in 2023 and beyond.

Conclusion

The collective claims segment has been a growing and fast-evolving feature of the English litigation landscape over recent years, a trend that will continue over the next twelve months. We expect to see claimants continue to look for creative ways to deploy existing procedural mechanisms to advance collective claims in respect of a range of issues, with a continued focus on claims against Big Tech and in respect of ESG-related matters.

Key contacts for Collective Claims

2 Case 1403/7/721: Dr Rachel Kent v Apple Inc. and Apple Distribution International Limited; and Case 1468/7/7/22: Mr Justin Gutmann v Apple Inc., Apple Distribution International Limited, and Apple Retail UK Limited.

3 Case 1408/7/7/21: Elizabeth Helen Coll v Alphabet Inc. and Others; and Case 1572/7/7/22: Claudio Pollack v Alphabet Inc. and Others.

4 Case 1568/7/7/22: Julie Hunter v Amazon.com, Inc. and Others.

5 Case 1527/7/7/22: Alex Neill Class Representative Limited v Sony Interactive Entertainment Europe Limited; Sony Interactive Entertainment Network Europe Limited; and Sony Interactive Entertainment UK Limited.

6 Case 1382/7/7/21: Consumers' Association v Qualcomm Incorporated.

7 Case 1433/7/7/22: Dr Liza Lovdahl Gormsen v Meta Platforms, Inc. and Others.

8 Dr Liza Lovdahl Gormsen v Meta Platforms, Inc. and Others [2023] CAT 10, paragraphs 57 and 62.

9 For further reading, see our article on the Meta CPO: https://www.traverssmith.com/knowledge/knowledge-container/meta-cpo-hearing-the-start-of-a-new-era-for-mass-data-privacy-claims/.

10 Municipio de Mariana v BHP Group plc (formerly BHP Billiton Plc) [2021] EWCA Civ 1156.

11 We explore this decision further in this piece.

12 The GLO mechanism has also been used to advance claims in respect of personal data breaches: see the GLO made in The British Airways Data Event Group Litigation dated 11 October 2019 (Weaver & Ors v British Airways plc; Claim No BL-2019-001146).

13 [2021] UKSC 50 ("Lloyd v Google").

14 A similarly restrictive approach to the "same interest" requirement was taken in Jalla & Anor v Shell International Trading & Anor [2021] EWCA Civ 1389, in that case in the context of a mass claim for damages arising from environmental harm.

15 Commission Recovery v Marks & Clerk [2023] EWHC 398 (Comm).